Paper No : 205

Presentaation Topic : The Globalization of Indian Literature: A Critical Examination of Chetan Bhagat’s Works

Presentation Video :

Paper No : 205

Presentaation Topic : The Globalization of Indian Literature: A Critical Examination of Chetan Bhagat’s Works

Presentation Video :

Paper No : 204

Presentation Topic : Lens of Inequality: A Cinematic Study of Frames in Article 15

Presentation Video :

Paper No : 203

Presentation Topic : Friday as Subaltern Character

Presentation Video :

Paper No : 202

Presentation Topic : Exploring Indian Identity and Culture in Jayanta Mahapatra's Poetry

Presentation Video :

Paper No: 201

Presentation Topic : Divine Feminine Power in 'Savitri': Savitri as an Avatar of Shakti

Presentation Video :

Hello Everyone, This blog is a part of thinking activity Which assigned by Prakruti Ma'am.

Introduction:-

Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre celebrates female independence within a patriarchal society, while Jean Rhys's Wide Sargasso Sea reimagines the story from a postcolonial perspective, giving voice to the marginalized and challenging the dominant narrative.

Share your thoughts about the concept of the hysterical female (madwoman in the attic) with reference to Rhys' novel. How is insanity/madness portrayed in the narrative of the text?

Ans.

The concept of the "hysterical female" or the "madwoman in the attic," rooted in feminist literary criticism, plays a significant role in Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea. This trope, originally popularized by Gilbert and Gubar in The Madwoman in the Attic (1979), identifies madness as a manifestation of the systemic repression of women in patriarchal societies. In Rhys’s novel, madness is intricately tied to themes of colonialism, patriarchy, identity, and trauma, as it reimagines the backstory of Bertha Mason (renamed Antoinette Cosway) from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre.

Rhys subverts the "madwoman in the attic" trope by giving Antoinette a voice and history, challenging her depiction as merely a caricature of madness in Jane Eyre. Instead of being dismissed as irrational, her insanity is contextualized within a framework of systemic oppression. Madness becomes a lens through which Rhys critiques both colonial and patriarchal ideologies.

Provide a comparative analysis of Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre and Rhys' Wide Sargasso Sea. How are both the texts uniquely significant in capturing female sensibility?

Ans.

Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre (1847) and Jean Rhys's Wide Sargasso Sea (1966) reveals distinct approaches to capturing female sensibility, particularly regarding themes of identity, autonomy, and the impact of patriarchy. While Jane Eyre focuses on the journey of a singular protagonist in asserting her individuality, Wide Sargasso Sea amplifies the marginalized voice of Bertha Mason (Antoinette Cosway), a character silenced in Brontë’s narrative, providing a postcolonial and feminist critique of the original text.

Which aspects of Wide Sargasso Sea can be considered postcolonial? Briefly discuss some of the major elements of the text which reflect the postcolonial condition.

Ans.

Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea is a quintessential postcolonial text, engaging with themes of colonial history, racial and cultural identity, and the systemic oppression tied to imperialism. As a reimagining of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre from the perspective of Bertha Mason (renamed Antoinette Cosway), it critically examines the erasures and silences of colonial subjects in European literary traditions.

In conclusion, Jane Eyre and Wide Sargasso Sea offer distinct yet interconnected explorations of female identity and societal constraints. While Brontë’s novel celebrates resilience and empowerment within a patriarchal framework, Rhys’s text reclaims the marginalized voice of Bertha Mason, challenging colonial and gendered silences in the literary canon. By critiquing the socio-political forces behind madness and identity erasure, Wide Sargasso Sea enriches the discourse initiated by Jane Eyre, offering a deeper understanding of female experiences across different cultural and historical contexts. Together, they provide a nuanced examination of gender, identity, and resistance.

Thank you for visiting...

Edward Said's Orientalism:

Homi Bhabha's Hybridity

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak's Subaltern Studies

Personal Information

Name : Khushi R. Rathod

Batch : 2023-25

Roll No : 16

Enrollment Number : 5108230039

Semester : 3

E- mail : khushirathod1863@gmail.com

Assignment Details

Paper No : 205A

Paper Code : 22410

Paper Name : Cultural Studies

Topic : The Intersection of Identity and Power in Cultural Studies: Analyzing Postcolonial Narratives

Submitted to : Smt.S.B.Gardi, Department of English,MKBU

This paper explores the intricate relationship between identity and power in cultural studies, focusing on postcolonial narratives. These narratives delve into the complexities of colonial and postcolonial contexts, highlighting the fragmented identities and power hierarchies that define the experiences of the colonized. Employing theoretical frameworks such as Homi Bhabha's hybridity and Michel Foucault's discourse on power, the study examines the works of postcolonial writers like Chinua Achebe, Salman Rushdie, Jean Rhys, and Edwidge Danticat. The paper analyzes themes such as linguistic resistance, intersectionality, trauma, and subaltern voices, emphasizing how these narratives challenge Eurocentric canons and reclaim marginalized identities. By interrogating the impacts of colonialism and the resilience of cultural identities, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of identity formation and power dynamics in a globalized, postcolonial world.

Key Words :Postcolonial Narratives, Identity, Power Dynamics, Hybridity, Cultural Studies, Subaltern Voices, Intersectionality, Trauma, Eurocentrism, Resistance, Globalization

The concept of identity and power is pivotal in cultural studies, particularly within postcolonial narratives. These narratives explore the complex interactions between colonizers and colonized, highlighting how identity and power structures are both challenged and perpetuated. Postcolonial writers use literature to critique colonial legacies, represent marginalized voices, and reconstruct histories that have been obscured. By examining works from postcolonial writers such as Chinua Achebe, Salman Rushdie, and Jean Rhys, this paper analyzes how identity is shaped by power dynamics and how these narratives challenge hegemonic structures.

The analysis of postcolonial narratives is underpinned by diverse theoretical frameworks that elucidate the interdependence of identity and power:

Edward Said's Orientalism: Said's concept of Orientalism underscores the power-knowledge nexus, where the West constructs an "Orient" as the exotic, inferior "Other." This artificial binary fosters imperial control by defining and dominating the identity of colonized peoples.

Homi Bhabha's Hybridity: Bhabha introduces hybridity as a space where colonial and indigenous cultures intermingle, creating new, fluid identities. This process disrupts fixed notions of identity and resists colonial dominance through mimicry and ambivalence.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak's Subaltern Studies: Spivak's inquiry into subalternity addresses the erasure of marginalized voices within dominant power structures. Her critique interrogates whether the subaltern can truly "speak" within frameworks shaped by colonial and patriarchal forces.

Identity, in postcolonial contexts, is often fragmented and hybrid. The imposition of colonial culture creates a crisis of identity for the colonized, as they are caught between their native traditions and the enforced colonial norms. Homi K. Bhabha's concept of "hybridity" illustrates this duality, where colonized subjects navigate a "third space" that disrupts binary oppositions between the colonizer and the colonized.

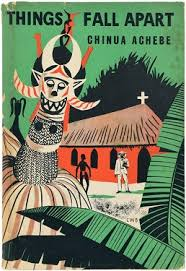

1. Disrupted Identities in Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart

Achebe's Things Fall Apart explores the collision of Igbo traditions with British colonial forces. The protagonist, Okonkwo, embodies the fragility of cultural identity amid colonial encroachment. Achebe critiques the cultural disruption caused by missionaries and colonial administrators, portraying the tragic fragmentation of Igbo society. The novel highlights how power—manifested through religion, language, and governance—erodes indigenous identity, creating a liminal space of cultural loss and adaptation.

Rhys's prequel to Jane Eyre rewrites the story of Bertha Mason, contextualizing her descent into madness through the lens of colonial oppression. Antoinette, the protagonist, embodies the hybridity of her Creole identity—a convergence of European and Caribbean influences. The novel critiques the exploitation and dehumanization of women in colonial systems, emphasizing how power dynamics intersect with gender and race to fracture identity. Antoinette's resistance to these forces, though ultimately tragic, underscores the complexity of identity negotiation in colonial contexts.

Devi's short story Draupadi centers on Dopdi Mejhen, an indigenous woman and revolutionary. Through Dopdi's resistance against state oppression, the narrative reveals the violent mechanisms of power that silence subaltern voices. Dopdi's defiance in the face of systemic violence reclaims her agency, challenging the patriarchal and colonial forces that seek to erase her identity. Devi's work underscores the resilience of marginalized communities and the necessity of amplifying subaltern voices in postcolonial discourse.

Power dynamics in postcolonial narratives are intricately linked to the cultural hegemony established during colonial rule. By reshaping education, language, and social norms, colonial powers sought to maintain control over colonized populations. Postcolonial narratives often critique these mechanisms, revealing the ways in which power perpetuates inequality and erases cultural diversity.

Ngũgĩ's seminal work critiques the role of colonial education in undermining indigenous languages and cultures. By enforcing European languages as the medium of instruction, colonial powers devalued native identities, creating a sense of inferiority among the colonized. Ngũgĩ advocates for the reclamation of indigenous languages as a means of cultural resistance and identity preservation.

Roy's novel explores the intersection of caste, gender, and colonial legacy in shaping power dynamics. The characters Ammu and Velutha embody resistance against societal norms that perpetuate oppression. Through their tragic love story, Roy critiques the ways in which power operates through caste hierarchies and patriarchal structures, silencing voices that challenge the status quo.

Rushdie's novel examines the commodification of culture in postcolonial India, portraying the ways in which political power appropriates cultural symbols for nationalist agendas. The protagonist, Saleem Sinai, symbolizes the fragmented identity of postcolonial India, shaped by historical trauma and political manipulation. Rushdie's use of magical realism highlights the tensions between tradition and modernity, exposing the complexities of cultural identity in a globalized world.

While postcolonial narratives often depict the oppressive forces of power, they also celebrate acts of resistance and the reclamation of identity. Through storytelling, these narratives empower marginalized voices and challenge dominant ideologies.

Danticat's novel emphasizes the role of oral traditions in preserving cultural memory and resisting colonial erasure. Through the intergenerational experiences of Haitian women, the narrative portrays the resilience of cultural identity in the face of displacement and trauma. Danticat's work highlights the importance of storytelling as a tool for reclaiming agency and asserting cultural heritage.

Adichie's novel examines the intersection of gender, religion, and colonial legacy through the experiences of Kambili, a young Nigerian girl. The narrative critiques patriarchal and authoritarian power structures, portraying Kambili's journey toward self-empowerment. Adichie's emphasis on feminist resistance underscores the transformative potential of reclaiming identity in oppressive environments.

Ghosh's novel integrates environmental and cultural themes to critique the exploitation of marginalized communities and ecosystems. The narrative centers on the Sundarbans, where local traditions and ecological knowledge resist the encroachments of modernization and capitalist power. Ghosh's work underscores the interconnectedness of identity, power, and the environment, advocating for sustainable and equitable futures.

Postcolonial narratives often highlight how gender intersects with identity and power. Women, in particular, face layered oppression as both colonized subjects and gendered beings. Feminist postcolonial theory, as articulated by scholars like Gayatri Spivak, interrogates the silencing of women in colonial and nationalist discourses.

Walker's short story delves into the tensions between traditional and modern African American identities. Dee, one of the central characters, seeks to reclaim her heritage but does so in a way that alienates her family. The story critiques both patriarchal and cultural power dynamics, illustrating the complexities of identity formation.

Colonialism leaves deep psychological scars on individuals and communities. Postcolonial literature often explores the role of trauma and memory in shaping identity, reflecting the lasting impacts of colonial violence.

Coetzee's novel examines post-apartheid South Africa, focusing on power relations and the lingering effects of racial trauma. The characters’ struggles with identity reflect the nation’s ongoing process of healing and reconciliation. Through this lens, identity becomes a site of both individual and collective memory.

The intersection of identity and power in postcolonial narratives is a rich site of inquiry that illuminates the complexities of cultural transformation and resistance. By examining the mechanisms of colonial control and the resilience of marginalized voices, these narratives offer profound insights into the enduring impacts of power on identity. Through storytelling, postcolonial authors reclaim agency, challenge hegemonic structures, and envision alternative possibilities for cultural and social justice. As Cultural Studies continues to evolve, the analysis of postcolonial narratives remains vital in understanding and addressing the dynamics of power and identity in our globalized world.

Reference :

Astrick, Tifanny. “(PDF) Patriarchal Oppression and Women Empowerment in Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's Purple Hibiscus.” ResearchGate, 2019, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334674218_Patriarchal_Oppression_and_Women_Empowerment_in_Chimamanda_Ngozi_Adichie's_Purple_Hibiscus. Accessed 19 November 2024.

Batool, Javairiah, and Amber Hafeez. “An Analysis of the Representation of Hybrid Culture and Transculturalism in Jean Rhys’s "Wide Sargasso Sea."” Researchgate, 2022, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/367644162_An_Analysis_of_the_Representation_of_Hybrid_Culture_and_Transculturalism_in_Jean_Rhys's_Wide_Sargasso_Sea. Accessed 19 November 2024.

Bhushan, Vishwa. “(PDF) An Ecology and Eco-Criticism in Amitav Ghosh's The Hungry Tide.” ResearchGate, February 2021, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/363061231_An_Ecology_and_Eco-Criticism_in_Amitav_Ghosh's_The_Hungry_Tide. Accessed 19 November 2024.

Giri, Pradeep Kumar. “Salman Rushdie's Midnight’s Children: Cultural Cosmopolitan Reflection.” Nepal Journals Online, 1 January 2021, https://nepjol.info/index.php/batuk/article/download/35349/27668/102913. Accessed 19 November 2024.

Kr, Kaushik. “Subaltern Voice In Mahasweta Devi's Draupadi.” Elementary Education Online, 15 December 2021, https://ilkogretim-online.org/index.php/pub/article/view/2178. Accessed 19 November 2024.

Nimer, Abdalhadi, and Abu Jweid. “(PDF) The fall of national identity in Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart.” ResearchGate, 2016, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/298710557_The_fall_of_national_identity_in_Chinua_Achebe's_Things_Fall_Apart. Accessed 19 November 2024.

Segall, Kimberly Wedeven. “Pursuing Ghosts: The Traumatic Sublime in J. M. Coetzee's Disgrace.” Researchgate, December 2005, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236704852_Pursuing_Ghosts_The_Traumatic_Sublime_in_J_M_Coetzee's_Disgrace. Accessed 19 November 2024.

Sharma, Dr Shreeja Tripathi. “(PDF) Alice Walker's Everyday Use: Decoding Cultural Inheritance and Identity.” ResearchGate, January 2022, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359264824_Alice_Walker's_Everyday_Use_Decoding_Cultural_Inheritance_and_Identity. Accessed 19 November 2024.

Sunny, Ferdiansyah, and Marudut Bernadtua Simanjuntak. “Article Review Negotiating with Trauma in Novel Breath Eyes Memory by Edwidge Danticat.” Researchgate, June 2022, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/361332805_Article_Review_Negotiating_with_Trauma_in_Novel_Breath_Eyes_Memory_by_Edwidge_Danticat. Accessed 18 November 2024.

Images : 11

Words : 1888

Thank you for visiting….

22409: Paper 204: Contemporary Western Theories and Film Studies

"Sacred Earth: Ecocritical Reflections on Nature in Indian Mythology"

Table of Contents :

Personal Information

Assignment Details

Abstract

Keywords

Introduction

Ecocriticism and Its Relevance to Indian Mythology

Indian Mythology and Environmental Consciousness

Sacred Earth in Indian Mythology

Panchtattva: The Five Elements and Unity with Nature

Panchtattva: The Five Elements and Unity with Nature

Nature as Divine in Indian Epics

Sita: The Earth Mother

Karna: The SunWarrior

Shakuntala: The Forest’s Daughter

Forests as Spaces of Wisdom and Renewal

Symbiosis in Mythological Narratives

Ecological Warnings and Moral Imperatives

Environmental Destruction in the Mahabharata

The Cyclical Nature of Time and Ecological Awareness

Indian Mythology as a Framework for Modern Ecological Ethics

Biocentrism and Reverence for All Life Forms

Inspiring Modern Environmental Movements

Conclusion

Personal Information

Name : Khushi R. Rathod

Batch : 2023-25

Roll No : 16

Enrollment Number : 5108230039

Semester : 3

E- mail : khushirathod1863@gmail.com

Assignment Details

Paper No : 204

Paper Code : 22409

Paper Name : Contemporary Western Theories and Film Studies

Topic : "Sacred Earth: Ecocritical Reflections on Nature in Indian Mythology"

Submitted to : Smt.S.B.Gardi, Department of English,MKBU

Abstract

This assignment explores the ecological themes in Indian mythology through an ecocritical lens, focusing on the deep reverence for nature embodied in ancient Hindu texts like the Ramayana, Mahabharata, Vedas, and Puranas. Indian mythology personifies nature in various forms, attributing divinity to natural elements and promoting a harmonious relationship between humans and their environment. By examining these texts, this paper seeks to reveal how Indian mythology offers timeless wisdom for ecological conservation, emphasizing a biocentric worldview that can serve as a guide to contemporary environmental challenges.

Keywords: Indian mythology, ecocriticism, Panchtattva, Ramayana, Mahabharata, nature worship, biocentrism, environmental ethics, sacred rivers, sustainability

Introduction

Indian mythology, an intricate tapestry of ancient tales, philosophies, and teachings, has long shaped the cultural and spiritual ethos of the Indian subcontinent. Ecocriticism, a modern field examining the relationship between literature and the environment, provides a framework for analyzing these narratives, revealing how Indian mythology fosters an ecological consciousness essential to sustainable living. This paper explores how nature is revered in Indian mythology, showcasing a deep-seated biocentrism that emphasizes humanity’s moral obligation to preserve the natural world. By investigating ecocritical themes in key mythological texts, we can better understand the enduring bond between humanity and nature and draw lessons for contemporary ecological crises.

Ecocriticism and Its Relevance to Indian Mythology

Ecocriticism, defined as “the study of the relationship between literature and the physical environment” (Glotfelty), aims to bridge cultural expressions and ecological values Through an ecocritical lens, we see that Indian mythology embodies environmental ethics, viewing nature as sacred rather than an object of exploitation.

Indian Mythology and Environmental Consciousness

The mythology of India spans Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and regional folk traditions, with Hindu mythology particularly rich in ecological symbolism. The Vedas, Ramayana, Mahabharata, and Puranas shape Indian perspectives on nature, portraying it as a divine force intertwined with humanity. Scholars have increasingly turned to these texts, not only to uncover traditional environmental philosophies but to consider their potential in shaping a sustainable future.

Sacred Earth in Indian Mythology

Panchtattva: The Five Elements and Unity with Nature

Central to Hindu cosmology is the concept of Panchtatva—the five elements of earth (prithvi), water (apas), fire (agni), air (vayu), and aether (akasha)—which compose both the human body and the environment. These elements underpin various life stages, binding humans with the natural world through ritualistic practices. As Panchtatva represents a holistic connection to nature, it advocates for the preservation of environmental harmony.

Divine Rivers and the Sanctity of Water

In Hindu mythology, rivers like the Ganges and Yamuna hold immense spiritual significance, symbolizing purity, rejuvenation, and forgiveness. Texts like the Rigveda attribute divine powers to these rivers, which are seen as both life-givers and purifiers. The Vedas express this sanctity in verses such as “May the Waters, the mothers, purify us,” personifying rivers as maternal figures who cleanse both physical and moral impurities. This reverence fosters a protective attitude toward water bodies, highlighting their importance in maintaining ecological balance.

Nature as Divine in Indian Epics

Sita: The Earth Mother

The Ramayana presents Sita as Bhumija or the “daughter of the Earth,” symbolizing fertility, patience, and resilience. Sita’s connection to the earth is profound, as she emerges from the earth and ultimately returns to it. Her trials in the forest, from exile to motherhood, reveal a life intimately connected with nature, demonstrating that humanity’s existence is bound to the cycles of nature. Her character embodies the nurturing, forgiving qualities of the earth, which absorbs human actions yet continues to sustain life

Karna: The SunWarrior

In the Mahabharata, Karna is described as Suryaputra (son of the Sun), symbolizing the life-giving yet impartial nature of the Sun. Karna’s innate armor, derived from the Sun, exemplifies the protective and benevolent attributes of nature. His sacrifice of this armor for the greater good reflects the selfless, all-giving nature of the environment. Karna’s character thus embodies the virtues of strength, endurance, and altruism—qualities essential to a balanced ecosystem.

Shakuntala: The Forest’s Daughter

In Kalidasa’s Abhijnana Shakuntalam, Shakuntala represents nature’s purity and innocence. Raised in an ashram amid the forest, her beauty and kindness parallel the undisturbed, serene qualities of nature. As Shakuntala grows, her connection to the forest mirrors humanity’s ability to thrive alongside nature. Her story emphasizes the forest’s role as a source of wisdom, shelter, and tranquility, aligning with Indian beliefs that the forest is a sanctuary for reflection and spiritual growth.

Forests as Spaces of Wisdom and Renewal

In Vedic and Upanishadic traditions, forests serve as realms for spiritual exploration, symbolizing the absence of societal constraints. The Aranyakas, or “forest texts,” highlight the belief that knowledge and enlightenment flourish in nature. Thapar notes that forests were revered as spaces “where the hierarchies and regulations of the grama were not observed”. Such views present forests as sacred ecosystems essential for mental and spiritual health, advocating for their preservation as refuges for biodiversity and inner reflection.

Symbiosis in Mythological Narratives

Mythological epics emphasize the symbiotic relationship between humans and non-human entities, portraying animals and plants as integral to human survival. In the Ramayana, for example, animals like Jatayu (a vulture) and Hanuman (a monkey god) assist Rama in his quest to rescue Sita, demonstrating an interspecies alliance. This symbiosis illustrates that human survival depends on other beings and that the destruction of biodiversity threatens the balance of existence.

Ecological Warnings and Moral Imperatives

Environmental Destruction in the Mahabharata

The Mahabharata warns against environmental degradation, particularly during the Kali Yuga (the last age of humanity). It predicts an era marked by droughts, dwindling natural resources, and human cruelty—a scenario that mirrors today’s ecological crises. The narrative cautions against greed and exploitation, urging humanity to uphold values of moderation and respect for nature.

The Cyclical Nature of Time and Ecological Awareness

Indian mythology’s concept of cyclical time, or Yuga, emphasizes that nature regenerates even as humanity faces the consequences of its actions. This cycle teaches that while destruction is inevitable, so is renewal. However, it underscores that respect for nature determines the length of each era’s prosperity, highlighting the need for sustainable practices to prevent premature environmental collapse.

Indian Mythology as a Framework for Modern Ecological Ethics

Biocentrism and Reverence for All Life Forms

Indian mythology advocates a biocentric approach, wherein nature is valued intrinsically rather than for its utility to humans. For instance, the Matsya Purana equates the planting of a tree to having ten sons, symbolizing the tree’s life-giving and protective qualities. Such values align with ecocritical principles that prioritize nature’s well-being, encouraging a shift from an anthropocentric to a more inclusive worldview.

Inspiring Modern Environmental Movements

Contemporary ecological initiatives in India, such as the Ganga Action Plan and the Chipko Movement, reflect the mythological reverence for rivers, trees, and forests. By recognizing the divine essence in nature, these movements emphasize the importance of preserving natural resources for future generations. Indian mythology’s ecological wisdom offers a cultural foundation for these efforts, underscoring the value of environmental stewardship.

Conclusion

Indian mythology, through its ecological consciousness, provides a valuable framework for understanding and addressing contemporary environmental challenges. The characters, narratives, and philosophies embedded in ancient texts illustrate a harmonious relationship between humans and nature, rooted in respect and reverence. As modern societies grapple with ecological degradation, these mythological perspectives offer timeless lessons on sustainability, biocentrism, and coexistence.

By revisiting Indian mythology through an ecocritical lens, we gain insight into the moral imperatives necessary to cultivate an environmentally conscious society. Indian mythology encourages us to see nature not as a resource to be exploited but as a sacred entity that deserves respect and protection. As we confront the urgent environmental crises of our time, the teachings of these ancient texts inspire a commitment to preserving the earth and its myriad forms of life, emphasizing that humanity’s future depends on its ability to coexist with, rather than dominate, the natural world.

Today, as the world faces issues like climate change, deforestation, and biodiversity loss, Indian mythology offers valuable insights into sustainable living. Movements like the Chipko Movement and the Ganga Action Plan, which draw on cultural reverence for forests and rivers, demonstrate how mythological values can inform contemporary ecological initiatives. These stories remind us that sustainable practices are essential to preserve natural resources for future generations. Indian mythology, therefore, provides a cultural and spiritual foundation for environmental conservation, inspiring modern societies to respect and protect nature.

Reference :

Badola, Anukriti, and Ambuj Kumar Sharma. “(PDF) Indian Mythology and Ecocriticism.” ResearchGate, 22 October 2024, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/384671086_Indian_Mythology_and_Ecocriticism. Accessed 13 November 2024.

Image : 6

Words : 1601

Thank You for visiting….

Code 22416: Paper 209: Research Methodology Plagiarism: Trap –Consequences,Forms, Types, and How to Avoid It Table of Content : Personal...